From the History Education Program Team (To Our Majors and Alumni):

We are living in difficult times.

How do we make sense of the issues we currently face as historians, educators, Americans, and global citizens? From COVID, to the stories of harrassment and attacks on Asians and Asian Americans, to the continual caging of children detained at the U.S.-Mexico border, to the never-ending shootings at school campuses, to the senseless killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery (and so many others before them) ... how can we help all of our students navigate these difficult times through the teaching of history/social studies?

As history/social studies educators, it might seem like a monumental task to figure out ways to deal with the various crises in our country. As human beings, it is natural to feel enraged, scared, confused, and convicted all at once. Further complicating everything, we enter a summer season trying to figure out how to make history and social studies relevant and useful in the age of remote learning due to COVID-19. Still, we shouldn't be afraid to tackle the most difficult subjects in our curriculum, including the historical and continuing role of racism and injustice in our society. It is our job to more deeply explore and contextualize this past and to do so in ways that will help create more thoughtful and empathetic citizens in the future.

Our encouragement is to reconsider the role of history and social studies education to change lives. It is within our reach to use lessons of the past and present to teach empathy, compassion, equality, justice, and respect for others. These are hallmarks of character education, whose traits are already found in many (if not all) state social studies standards. Use this summer season to construct a meaningful curriculum that is less focused on the cool trivia of history, or what "works for me," and instead pushes us to be better educators, historians, and mentors. In other words, teach about the past in ways that can inform our present moment and help our students build a better future.

Below are statements from educational leaders, information, and resources that can help you get started (plus some helpful resources for teaching in the time of COVID 19). There is much more, of course. We hope you make it a priority this summer to research teaching strategies and online resources that can help you develop a curriculum that contributes toward a shared mission of improving our world.

- The HEP Team

Character education in NC Schools

Statement from the Dean of RCOE

NCSS Statements on Racial Harrassment & Violence

Teaching Tolerance & Culturally Responsive Instruction (in the Age of Distance Learning)

Character Education - Student Citizen Act of 2001

On their website, the NC Department of Public Instruction defines Character Education as "an effort to help schools teach students to be good citizens. It is a goal for schools, districts, and states to teach students the important values that we all share. Some of these values include: respect; responsibility; integrity; perseverance; courage; justice and self-discipline." The Character Education Program addresses issues that are of concern in our society and our schools and is [officially] taught within the Social Studies Standard Course of Study. However, we know that the responsibility to teach and model character education rests with every teacher, staff member, and administrator in our schools.

More from NCDPI: "In the fall of 2001, the Student Citizen Act of 2001 (SL 2001-363) was passed into law by the NC Legislature. This act requires every school district to support character education teaching with buy-in from community. This act demonstrates that promoting character in our children is the foundation of education in our state. We want to provide the leadership, resources, and support to develop good citizens. NCDPI has developed resources to help districts and schools with teaching character development. These resources help schools and communities develop good lesson plans and strengthen programs."

Visit the Character Education Google Site for more information and to access resources.

Below is a statement from Dr. Melba Spooner, Dean of the Reich College of Education:

"I am struggling, I say that because I know words are inadequate right now, but I also know that silence is not an option, and I care about each of you. To our Black faculty, staff, students, and community friends and partners, I am so sorry for the pain you are experiencing. Your college is here to stand with you and support you.

I want to acknowledge the grief and pain that is being felt across our country and in our local communities. The recent killings of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and most recently George Floyd - these are examples of the systemic racial injustice that plagues our country. The news/media venues and headlines are full of stories and words sharing the pain and the anger. It is heartbreaking and overwhelming, but we cannot be silent in word, or deed.

Our collective work as educators, as a college, becomes even more important now. We must work to commit to not only acknowledging the problematic histories and practices that have perpetuated racial injustice, but we must commit to supporting educational opportunities for individuals and communities that are impacted by these legacies of racism.

As a college of education with a commitment to socially just practices, we have a responsibility to ask – what can we do, what must we do? Even more, we must lead in sharing our voices condemning systemic racial injustice.

I am grateful for each of you. I am optimistic in our future as we focus together on our commitment to educational justice and equity and for the humanity of every person. I continue to work through my role as a leader in this. I know words are not enough. If you need support in a particular way during this time, or into the future please let me know."

Press releases from the National Council for Social Studies:

1. NCSS Condemns Killing of George Floyd & Countless Black People - In response to the death of George Floyd, National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS) condemns the use of excessive violence or force, or extrajudicial processes, used discriminately by law enforcement against blacks in America when investigating or enforcing probable or non-probable causes of infractions, misdemeanors, or felonies. These actions are against the civic values and practices we teach all students through social studies education.

NCSS President Tina L. Heafner, Ph.D., expressed, “We are outraged by the use of violence that resulted in the death of George Floyd while being detained by Minneapolis law enforcement this week. Our hearts and sympathy are with the Floyd Family, the residents of Minneapolis, and all grieving Americans. NCSS strives to promote human rights and justice for all human beings regardless of race, sex, nationality, ethnicity, language, religion, or any other status. Mr. Floyd’s death along with the recent killings of two other black people, Ahmaud Arbery (who was shot after being pursued by white men near Brunswick, GA) and Breonna Taylor (who was killed by police officers in Louisville, KY, during a “no-knock” raid of her apartment), are unremitting reminders of deep-seated racism and institutionalized violence against people of color in America. This ongoing injustice of racialized police brutality involving countless black people must stop. Moreover, this systemic pattern of dehumanizing, criminalizing, and terrorizing people of color, and in particular black men, women, and children must end.”

2. A National Council for the Social Studies Response to Anti-Asian Harassment and Violence During COVID-19 (May 18, 2020) - Since the first identified case of COVID-19 was declared in the United States on January 15, incidents of verbal and physical harassment against Asians and Asian Americans have sharply increased (Yan, Chen, & Nuresh, 2020). On March 16th, President Donald Trump referred to COVID-19 as “the Chinese Virus” in a controversial tweet (Kuo, 2020), defending his phrasing and denying that it might be racist for several days before publicly declaring he would refrain from repeating the phrase (Vasquez, 2020). From mid-March, in one month almost 1,500 physical and verbal attacks against Asian Americans were reported. People of Asian descent have been beaten, spat on, yelled at, insulted, and faced bodily harm from coast to coast. Asian American students have been called “coronavirus,” told to “go back to China,” and physically assaulted.

History shows this is not the first time the United States has witnessed a surge of anti-Asian discrimination in a time of public health crisis . In the wake of the 1876 outbreak of smallpox in California, Chinatowns were labeled as laboratories of infection and subjected to quarantine. During the 1900 bubonic plague outbreak, government officials in California and Hawaii also racialized the epidemic. They quarantined Chinatowns, sprayed the homes of Chinese residents with carbolic acid, forced Chinese residents to shower at public stations, and burned down their homes. A Chinatown in Orange County California was also burned down in 1906 when city officials viewed Chinese residents as threats to public health for the spread of leprosy. More recently, a similar pattern of racializing disease and fomenting anti-Asian discrimination occurred during the 2003 SARS epidemic and is evident now during the COVID-19 pandemic.

While fueled by the fear of disease and anti-Chinese/Asian rhetoric by politicians, the uptick of anti-Asian violence during a disease outbreak is rooted in longstanding biases toward Asian Americans. Soon after Asians arrived on U.S. soil, Asian immigrants were racialized as uncivilized, filthy, and dangerous to “Americans .” Depicted as the Yellow Peril who were dirty and dangerous to the United States as a white nation, Asian immigrants encountered discriminatory orders in housing, schooling, employment, marriage, and political participation. And in a time of public health crisis, wartime, or economic downturn, Asian Americans have often become a target of hate crimes and discrimination, as was the case in the Chinese massacre of 1871, Japanese American incarceration during World War II, the killing of Vincent Chin in 1982 during an economic downturn, discrimination against South Asian Americans, Arab Americans, and those perceived to be Muslim in the wake of September 11, 2001, and again today during the COVID-19 pandemic. The National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS) strongly condemns this discrimination and violence against Asian Americans. Furthermore, NCSS urges those in the public sphere to recognize the harm that is occurring and to engage in education about the impact of discrimination and violence on our citizens.

Role of Social Studies Education

This history and the current resurgence of Anti-Asian violence due to the COVID-19 pandemic signals the urgency of racial literacy education. As the home of democratic citizenship education, social studies educators have a duty to address race and racism. Our young and future citizens need the knowledge and skills to critically read, call out, and act against racism and racial violence in all its forms, especially during a time of crisis. COVID-19 is the newest episode in U.S. history in which a marginalized group is scapegoated and discriminated against during a public health crisis . Earlier, Irish immigrants were blamed for the cholera outbreaks in the 1830s. Then, Jewish immigrants were scapegoated for tuberculosis in the late 19th century, Italian immigrants for polio in the early 20th century, Haitian Americans for HIV in the 1980s, Mexican Americans for swine flu in 2009, and West Africans for Ebola in 2014. Informed and engaged citizens of a democratic society should know that a time of crisis requires solidarity, humanity, and hope, not hysteria or hatred. Only together can we “flatten the curve” of this pandemic, and only together can we prevent a wave of hate crime from arising. While racism and racialization of disease are not new to the United States, we can imagine and must promote a different kind of response through our teaching.

Social studies scholars and teacher educators whose research centers on the teaching of Asian American histories and Asian American representation are painfully aware of the effects of recent anti-Asian harassment on Asian American communities and of the longstanding absence of Asian American representation and histories in P-12 social studies curriculum. Asian Americans are woefully underrepresented in social studies textbooks (Suh, An, & Forest, 2015), standards (An, 2016), and children’s literature (Rodríguez & Kim, 2018). In the face of such sparse representation in the curriculum, media portrayals of Asians and Asian Americans as exotic Others serve as a potent influence to the popular imagination. While it is necessary to recognize the long history of anti-Asian racism in the United States, it is also vital that educators provide examples of Asian Americans showing agency and actively engaging in efforts to overcome this health and social crisis. For example, Sikhs, who are predominantly South Asian American, are providing massive food support across the country and Filipina/o nurses comprise a significant portion of the U.S. nursing force.

On May 11th and 12th, 2020, PBS debuted Asian Americans, the first major comprehensive documentary about Asian Americans, from the earliest arrivals to the United States in the 1800s to the present. The documentary is accompanied by an educational guide to which several NCSS College and University Faculty Assembly (CUFA) members have contributed lessons (see https://advancingjustice-la.org/what-we-do/curriculum-lesson-plans/asian-americans-k-12-education-curriculum ). Used alongside resources like those listed below, social studies educators can begin to include Asian American histories across the curriculum broadly, especially in conversations related to race and racism.

Resources

Below, we have curated a collection of resources about COVID-19, anti-Asian/Asian American harassment, and anti-Asian/Asian American racism for social studies educators interested in learning more about these histories and contemporary experiences. We are particularly mindful of the need to ensure that Asian American voices are included in these resources. We urge social studies educators to remind their students to seek #OwnVoices that emerge directly from the communities of focus, rather than relying on outsider and/or secondary sources of information.

- Yellow Peril Open-Source Syllabus, Curated by Dr. Jason Chang

- Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center

- Asian American Racial Justice Toolkit

- Asian Americans Advancing Justice Stand Against Hatred Reporting Website

- Anti-Asian Racism and COVID-19, Created by Dr. Jennifer Ho

- Coronavirus: Fostering Empathy in an Interconnected World, by Morningside Center

- Let’s Stop the Scapegoating during a Global Pandemic, by ACLU

- Coronavirus: Protect Yourself and Stand Against Racism, by Facing History and Ourselves

- Speaking Up Against Racism Around the New Coronavirus, by Teaching Tolerance

Teaching Tolerance & Culturally Responsive Instruction (in the Age of Distance Learning)

Common Sense Education offers a collection of resources for social justice- and equity-focused educators. These are great resources for your classrom! One particular blog post is also very useful ...

How to Develop Culturally Responsive Teaching for Distance Learning - Amielle Major (May 19, 2020)

The coronavirus pandemic and school closures across the nation have exposed deep inequities within education: technology access, challenges with communication, lack of support for special education students, to name just a few. During this crisis, there are still opportunities to provide students with tools to help them be independent learners, according to Zaretta Hammond, author of Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain.

The classroom is where so much of the focus on learning has been placed, but there are opportunities to develop learning routines at home. This won’t mean sending home the same materials a student would have in class, but thinking about what a student needs in order to have agency over their learning in any situation.

Hammond shared three design principles of culturally responsive instruction that can be used to support students’ cognitive development from afar in her webinar, “Moving Beyond the Packet: Creating More Culturally Responsive Distance Learning Experiences.” She said it’s important to stay focused on the student and offer small but high-leverage practices that maintain student progress and increase intellectual capacity during this time. She said these tips and activities also work for students without reliable access to technology and the internet.

First, what is culturally responsive instruction?

Shared language matters and there’s a lot of confusion about culturally responsive teaching. At its core, culturally responsive instruction is about helping students become independent learners. Culturally responsive instruction should:

- Focus on improving the learning capacity of students who have been marginalized educationally because of historical inequities in our school systems.

- Center around both the affective and cognitive aspects of teaching and learning.

- Build cognitive capacity and academic mindset by pushing back on dominant narratives about people of color.

“Culturally responsive instruction doesn't mean you're only mentioning issues of race and implicit bias," she said. "It means that you’re also focused on building brainpower by helping students leverage and grow their existing funds of knowledge.”

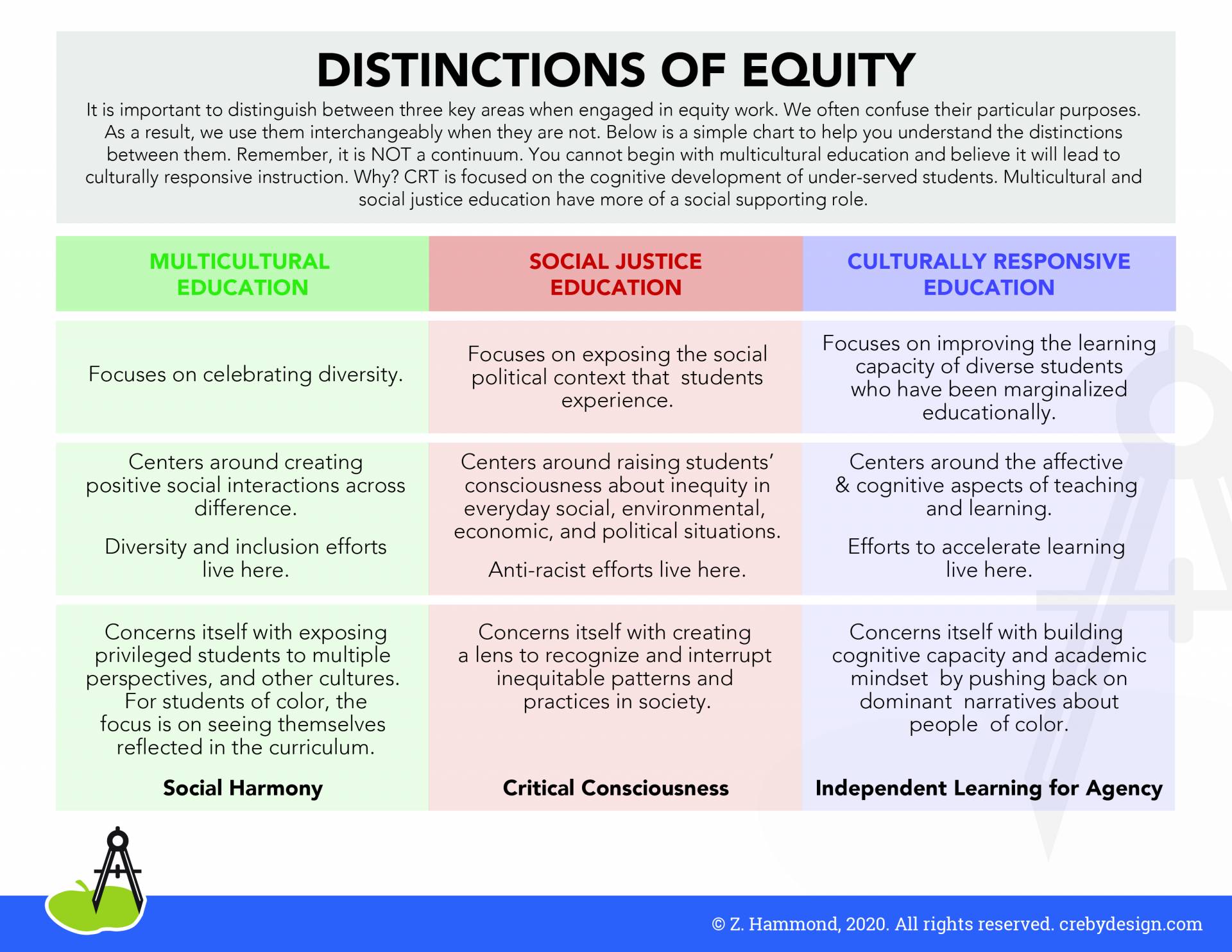

Hammond distinguishes the differences between culturally responsive education, multicultural education and social justice education. Each is important, but without a focus on building students’ brain power, they will experience learning loss.

[Click to read the full post at KQED Mind/Shift]